10. Stations of the Cross, dir. Dietrich Bruggemann

9. The Wind Rises, dir. Hayao Miyazaki

In The Wind Rises, we are not exposed to the full horror of the war to come, with talk of Japan's increasing militarism the only direct acknowledgement of the troubled times. Miyazaki renders this mood of oncoming loss as backdrop - and sometime companion - to Jiro's life. The Wind Rises is melancholy without ever feeling maudlin; an ode to the precarious beauty of flight and to Jiro's feverish optimism.

8. Calvary, dir. John Michael McDonagh

I wrote a little something for Grolsch Film Works on this year's preoccupation with religious films; somehow another Catholic has managed to get into my top 10 list. Irish director John Michael McDonagh gives us a depiction of a 'good priest' in this bleakly witty character study of a man out of time. Brendan Gleeson gives a devastating performance as the story unfolds into a moving exploration of dignity and duty. In a modern world of constant sarcasm and cruelty, Gleeson's priest shows a strength of character both rare and admirable.

7. Welcome to New York, dir. Abel Ferrara

6. Leviathan, dir. Sergei Zygavintsev

5. Under the Skin, dir. Jonathan Glazer

Jonathan Glazer's chillingly ambiguous sci-fi sees Scarlett Johansson, as a predatory alien being, prowling Glaswegian roads in a transit van. A subversive look at the thinly-veiled vulnerability of the female body, Under the Skin is mysterious and multi-faceted, allowing for any number of projections and readings. You can read what I made of the movie here.

Jonathan Glazer's chillingly ambiguous sci-fi sees Scarlett Johansson, as a predatory alien being, prowling Glaswegian roads in a transit van. A subversive look at the thinly-veiled vulnerability of the female body, Under the Skin is mysterious and multi-faceted, allowing for any number of projections and readings. You can read what I made of the movie here.

Filmed by Richard Linklater over the course of 12 years, as his stars grew older onscreen, Boyhood is essentially everything it's cracked up to be. As I said in my original review, it feels like a long dream, reveling in the smell of cut grass and childhood summers spent rolling around on the backyard trampoline. Punctuated by the distant tremors of adulthood, buoyed up by our loved ones, unafraid of the growing pains, it allows us to get the dirt under our fingernails. The passage of time is something all at once bright, terrifying, and unyielding. Linklater - and Mason, his young protagonist - face it with optimism. With all its boundless warmth and sensitivity, Boyhood captures life in a way that is quietly revolutionary. It feels like something that will endure.

3. Goodbye to Language 3D, dir. Jean-Luc Godard

If you're into revolutionary, mind-expanding, convention-exploding cinema - there's nothing better than Jean-Luc Godard in 3D. Here's what I said in my review:

If you're into revolutionary, mind-expanding, convention-exploding cinema - there's nothing better than Jean-Luc Godard in 3D. Here's what I said in my review:

To see late period work from Jean-Luc Godard is to prepare to surrender to impenetrability. And at eighty-two years old, he is as radical and confounding as he’s ever been. The 121st project from the chieftain of the French New Wave is as charmingly incorrigible and intellectually obtuse as Godard himself. Goodbye to Language is a freewheeling 3D exercise in vacillating montage and mutating images, continually defying any application of logic or structure.

In a rare recent interview, Godard stated that the ‘idea’ of Goodbye to Language is, in fact, to "escape from ideas". If it could be said to resemble anything at all, Godard’s film mostly emerges as some kind of exploration of the primordial, pre-linguistic muddle; the Lacanian mirror stage collapsing in on itself. If the premise is that language organises and structures our world by compartmentalising objects, ideas, and individuals in an ultimately limiting way, Godard repeatedly strikes out at the comprehensible features of that edifice.

2. The Wolf of Wall Street, dir. Martin Scorsese

A queasily mordant, hilarious, and undeniably questionable tale of late '80s avarice, Martin Scorsese's latest features Leonardo DiCaprio as Quaalude-addicted Wall Street dirtbag Jordan Belfort. Touches of Fellini and Billy Wilder combine in a swirlingly repetitive haze of sex, drugs, and white-collar crime. The rumble of suspicion and sniffiness around the film reached full peak last year around Oscars season, and ultimately it proved too unruly for that sort of rank and file success.

A queasily mordant, hilarious, and undeniably questionable tale of late '80s avarice, Martin Scorsese's latest features Leonardo DiCaprio as Quaalude-addicted Wall Street dirtbag Jordan Belfort. Touches of Fellini and Billy Wilder combine in a swirlingly repetitive haze of sex, drugs, and white-collar crime. The rumble of suspicion and sniffiness around the film reached full peak last year around Oscars season, and ultimately it proved too unruly for that sort of rank and file success.

Earlier this year, I spoke to Kubrick on the Guillotine editor Simran Hans about Scorsese's degree of complicity in the film's depiction of rampant misogyny. We disagreed fundamentally about where the film was coming from, but I did mention that I'd be unlikely to return to it very often. I think it's worth pointing out that I was wrong - I've seen it several times since, and each viewing has proven it to be compellingly chewy and complex. Simultaneously damning and self-congratulatory, nauseating and thrilling, The Wolf of Wall Street proves fascinating on repeat viewing.

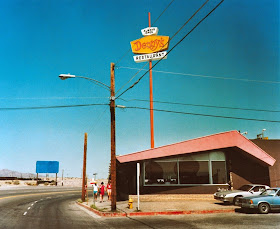

1. Inside Llewyn Davis, dir. Joel + Ethan Coen

Honourable mentions go to: Grand Budapest Hotel, Jodorowsky's Dune, Mr. Turner, Gone Girl, + Nightcrawler.

.jpg)

%2B(1).jpeg)

.jpeg)